by Lise Puyo

by Lise Puyo

On Tuesday, Marie Pelletier, who manages the Archives du Séminaire de Nicolet (Nicolet Seminary) welcomed us for a whole afternoon to examine the two wampum belts in their collections. One of them is entirely made of black glass beads.

Now, one might argue that if it is not shell, it is not a wampum belt. Yet, being made of glass beads does not necessarily mean the belt was not used in a meaningful way. With the wampum belts we have seen so far, we can make a few general observations about the prevalence of shell and glass. Although white shell beads are said to have been more numerous, purple shell beads are far more common than we would have expected. Glass beads were supposedly used as replacements for the shell material out of scarcity. If this is so, then the remaining collections seem to indicate that white shell beads were more scarce (or perhaps more meaningful) than purple shell beads. At Harvard Peabody, we discovered that glass beads were most often found in white designs. In the collections we visited, there were only a few belts with a white background. The sheer volume of purple shell in collections suggests that when Native wampum makers wanted to use purple shell, they had access to an abundance of this material. The selective use of glass beads seems to evoke a particular intent, and maybe sends a particular message.

At the Dartmouth Powwow, while meeting with traders and contemporary wampum makers, we learned that there are at least two types of dark glass beads resembling wampum: Czech ones, dark blue and translucent, letting the thread appear inside the bead; and French ones, either dark blue or nearly black and opaque. At Nicolet, during our first long glance, it looked like one belt was entirely made of these very dark French glass beads. This would fit the pattern of settlement along the Saint Lawrence and in Canada in general. Those beads—often referred to as porcelain in the written documents—were commonly used as trade goods to exchange for furs and other articles coming from Indigenous people.

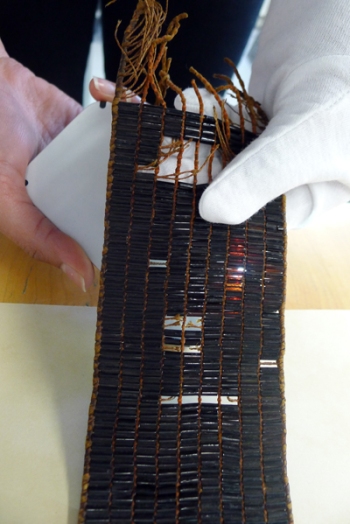

After looking at other aspects and spending time with this belt, however, we spotted a reddish hue, coming not only from the rawhide and linen, but also from the beads themselves. There was no sign of red ochre being rubbed onto the beads (as we saw on several other belts). Was the red color just a figment of our imagination? By shining a white light underneath the belts, we realized that these beads are not exactly black: they are a very dark shade of red. If this object was intended to be held up around a council fire, picture how the shimmering light would give it a dramatic aura. The belt would simply come alive.

After looking at other aspects and spending time with this belt, however, we spotted a reddish hue, coming not only from the rawhide and linen, but also from the beads themselves. There was no sign of red ochre being rubbed onto the beads (as we saw on several other belts). Was the red color just a figment of our imagination? By shining a white light underneath the belts, we realized that these beads are not exactly black: they are a very dark shade of red. If this object was intended to be held up around a council fire, picture how the shimmering light would give it a dramatic aura. The belt would simply come alive.

This close-up picture is helpful to show both the red color of the beads, and the red dye deeply soaked into the rawhide and linen warp and weft (giving them an orange hue). According to our observations so far, when red ochre is rubbed onto the belt, the warp is not tinted where pinched by the weft; it remains a pale color when the rest of the material is dusty red. Here, however, it seems that the leather was dyed before weaving the beads together, contributing to the overall reddish color of the belt.

We observed similar weaving techniques in several other belts so far: the warp is leather, the weft is plant fiber, and the long edges are wrapped with either dampened leather or rawhide so that the edge will harden as it dries, securing the weave. The ends of this dark glass belt are short and knotted together, which in wampum semiotics tends to indicate a closed, independent message, as opposed to long untied ends, which indicate that the message and dialogue can continue.

Some beads are missing on both ends. The fact that the weft is still in place, bearing witness for this bead loss, is specific to the Nicolet archives collections. In most other cases, when beads have been taken out, the weft was pulled out as well. These threads allow us to estimate the number of beads that are missing. This belt has seen no repair, unlike many of the other belts we have seen. A single black thread was added to it, but this thread does not help the weave or support any bead; it stands out, loosely tied. We believe it formerly held a collection tag, price tag, or explanation tag, perhaps added by a Nicolet curator after the 1870s.

This glass belt was clearly made with care and with intent: the weaving material reflects the color of the beads. The dark red beads have been darkened even further by the addition of a black ash-like coating that has partially soaked into the leather. It is constructed following the same Native weaving techniques observed on shell belts, but it does not use shell beads. As Dr. Bruchac observed, in wampum semiotics, the message is quite clear: dark beads (in the absence of any white beads) signal trouble, complexity, something powerful in a potentially harmful way. Those beads were apparently selected because of their ambiguity between black and red. The fact that they are foreign might indicate several things; we theorize that either it was made by Europeans, or it was made about Europeans.

According to the curatorial records at the Nicolet Seminary, this belt was given by the Blackfoot of Alberta to l’Abbé Georges-Henri Laforest during his sojourn in First Nations territory far to the west of Nicolet. This appears to be an early belt, using a style of glass bead common in the east, but uncommon in the west. If this belt originated in a region where wampum making is more common (the Northeast Atlantic coast, the Saint Lawrence seaway, or Haudenosaunee territory), it would have carried a very recognizable message that transcended language barriers: trouble is coming, involving foreigners. Since glass beads were common trade goods, the origin of the beads might identify which group this message would refer to: could a French bead represent the French?

With this belt, as with all the others, we are following Dr. Bruchac’s guidance in what appears to be a unique research approach. Our method is to examine every bead, every thread, every repair, and every bit of dirt and other material evidence while we talk around the belts, creating a visual and verbal thick description. Since we are coming with fresh eyes, and since we have familiarized ourselves with the various materials—quahog, whelk, conch, glass, sinew, brain-tanned leather, rawhide, hemp, linen—we often notice details that might have been overlooked before. The curators look on, and we invite them to share insights on how each belt has been handled and cared for, on other items it might relate to, and on any other information needing an inside eye. Only after close visual analysis do we turn to the examinations of provenance data and historical research that might track the movement of each belt from a community or event to its current environment. Since we only have a few hours to spend at each location, we gather as much data as possible while we are present with the wampum, and leave the written reports for our long debriefing sessions.

At each locale, museum curators have been delighted to hear stories about our previous discoveries and the insights gained from all of the different communities we’ve talked to: Indigenous wampum-keepers, wampum makers, antiquities dealers, and other museums. This has been a very collaborative effort so far, resulting in exciting new insights. However, as Dr. Bruchac reminds us, we need to recognize that our research may raise concerns, since museum wampum collections have been so carefully guarded, so poorly understood, and so hotly contested. She notes: “We are shining light into some dark corners of museological collections and recovering some provenance data that has been long missing. We have discovered evidence of Indigenous wampum-making techniques and messaging that both transcend and incorporate European materials. We expect to encounter contested Indigenous patrimony, and hope that we can encourage productive conversations about what each wampum belt has to tell us, and which Indigenous communities these belts are linked to.” All of us hope that our new museum colleagues will be as excited as we are that this restorative approach to research might hold the potential to solve some old mysteries, and heal some old wounds.